SPPC 2025 - Leiden

The 30th Symposium of Palaeontological Preparation and Conservation

Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, 26-27th June 2025

From Excavation to Exhibition

The 30th Symposium on Palaeontological Preparation and Conservation will be held in the Netherlands this year on 26-27th June.

The theme will be From Excavation to Exhibition and we hope to broaden our usual remit to include more aspects of the story of how geological collections end up on display in our museums, as well as their conservation and preparation.

Two days of presentations, tours and workshops, including a chance to hear about developing “Triceratops: the herd” exhibition from the Naturalis preparation team.

Day 1: Registration, presentations and posters (lunch included)

Day 2: Workshops and tours (lunch included)

This event is aimed at Fossil preparators, conservators, mount-makers, exhibition specialists, archaeologists, volunteers, students, curators

Workshops

You may attend multiple workshops on the second day of the symposium, but please indicate your first preference so we can get an idea of numbers.

- Radioactive bones, and how to deal with them

- How to start up a project for pyrite in a natural history collection

- 3D scanning and modelling and 3D printing

Staying in Leiden

IMPORTANT: The NATO 2025 Summit is taking place in Leiden on the 24th - 25th June, coinciding with SPPC. Therefore, it is recommended to book accommodation as soon as possible. A list of possible hotels is provided below:

- Fletcher Hotel

- Ibis Hotel

- IntercityHotel Leiden

- Golden Tulip & Tulip Inn Leiden Centre

Due to the NATO meeting, many roads in the city will be closed meaning the museum will be inaccessible by car for the duration of the meeting. Please plan your travel and accommodation accordingly.

If you would also like to meet up in the evening we suggest Stadscafe van der Werff.

Please scroll down to below the abstracts to register for attendance

Platform Presentation Abstracts

Excavation of terrestrial fauna from the early Cretaceous of Germany by Mayla Renz-Kiefel

|

25 years ago, fossil vertebrate remains were discovered in a quarry of Devonian limestone near the village of Balve in western Germany. Brought to the LWL-Museum of Natural History (Münster, Germany), they were identified as remains of iguanodontian dinosaurs. Since these fossils fall under conservation law in NRW, the museum was tasked in 2002 with conducting the excavation. Thousands of macroscopic fossils have been recovered since then, and even the smallest remains (0.5 mm) are being retrieved through screen washing. The site consists of a 125 Ma old karst filling inside the Devonian reef limestone. It has yielded a diverse mixture of animal remains, including turtles, amphibians, sharks, crocodiles, pterosaurs, carnivorous and herbivorous dinosaurs, and even mammals. Most remains are unidentifiable bone fragments up to a decimetre in length, which need to be stabilized in situ. Since the clay and silt matrix is too wet for the use of Paraloid, an alternative adhesive is used to consolidate crumbling bones. The fossils are retrieved within blocks of clay and prepared at the Museum in Münster. The unconsolidated clay matrix mostly allows for preparation with scrapers, brushes and water. More complicated finds can be revealed using air scribes. In addition to the collection of macrofossils, the entire sediment is softened in water for several hours and then screen washed through meshes of decreasing size. The resulting concentrate > 0.5 mm is picked under a stereomicroscope and yields the teeth and bones of very rare mammals. |

|

Towards the professionalization of palaeontological conservation: global challenges and the particular context of Mexico by Giselle Lorena Niño Silva

Palaeontological conservation is a field in constant evolution that demands an interdisciplinary approach to ensure the protection, preservation, and understanding of the fossil record. Yet, despite its importance, it remains largely unrecognized as a formal profession. This presentation reflects on the global need to professionalize palaeontological conservation, highlighting both widespread challenges and the particular conditions of the Mexican context. From the perspective of a conservator specialized in movable cultural heritage and fossil materials, the talk explores how the unique taphonomic processes of each specimen require tailored conservation approaches. In Mexico, a country rich in fossil diversity but marked by institutional and legal gaps, the role of the conservator in natural history collections remains insufficiently defined. However, this context also offers a fertile ground for the development of research in conservation and restoration, opening new lines of inquiry rooted in material specificity and context-based methodology.

|

The presentation emphasizes the value of collaborative work among professionals and institutions—whether museums, academic centres, or field laboratories—at both national and international levels. By sharing knowledge, experiences, and resources, the global community can foster innovation and advance ethical, methodological, and technical standards for palaeontological conservation. |

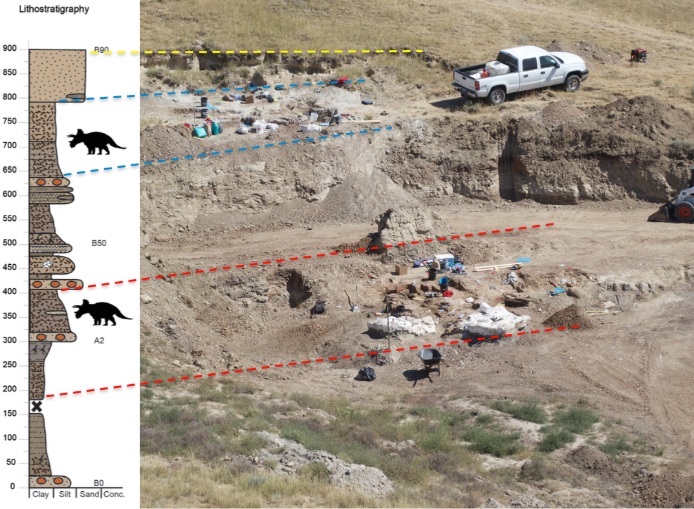

The Triceratops herd: from excavation to exhibition by Yasmin Grooters

Between 2013 and 2019, the Naturalis team excavated bones of a number of Triceratops individuals in the Lance Formation near Newcastle, Wyoming. Multiple individuals came from a disarticulated bonebed, while a single individual came from a bonebed four meters higher. We were able to reconstruct five skeletons with 350 of over a thousand bones that were found. What are the processes you come across when working on a project such as this? What preparation steps do you do before it is visible what type of bone you have, and then how do you divide these into the - hopefully, correct - individual? How do science and preparation work together to create an exhibit like Triceratops: the herd? This decade-long project ended up in presenting the first Triceratops herd on exhibition.

The excavation and preservation of a Chilean ichthyosaur fossil: the journey of Fiona by Cristina Gascó Martín, Erin E. Maxwell, Miguel Cáceres, Aymara Zegers, Irene Viscor Pagès, Luis Cotidio Chard, Andrés Pérez Marín, Jonatan Kaluza, Héctor Ortíz, Dean R. Lomax and Judith M. Pardo-Pérez

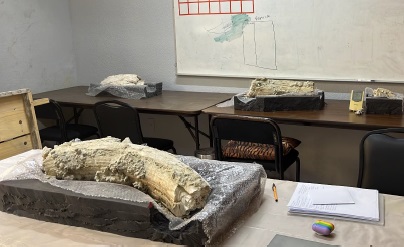

In March-April 2022 the first complete pregnant Hauterivian (Early Cretaceous) ichthyosaur was excavated in the Tyndall Glacier, Torres del Paine National Park in Chilean Patagonia. The extraction work took a month due to the challenging site and the hardness of the rock. As a result, five blocks containing the fossil were extracted and transferred to the Rio Seco Natural History Museum, in Punta Arenas, for preparation. Due to the media interest generated by the excavation of Fiona, the name given to the ichthyosaur as a result of the methodology used for the consolidation of the fossil material that left behind a green layer, the work with this fossil has been closely followed. Since the year of extraction, a process of documentation and analysis of the possibilities of preparation of the fossil has been carried out, as well as the cleaning and adhesion of some fragments. The preparation process is difficult due to the hardness of the rock and the difficulties differentiating the fossil from the rock. For this reason, it was decided in October-November 2024 to scan the specimen using computed tomography to see if it would help the restoration process.

|

To facilitate scanning, a matrix reduction intervention was done in order to reduce the weight of the blocks so that they could be moved and introduced into the CT scanner more easily. The scan was ultimately successful, indicating that this method can be used to supplement mechanical preparation in material from the Tyndall locality. In addition, cleaning, consolidation and adhesion of fragments were performed, leaving the specimen ready for potential future exhibition. |

Preserving fossils from the Pleistocene - take up the challenge by Susanne Klein

The conservation of subfossil bones, teeth and tusks is a challenge for us due to their subfossil preservation. The Pleistocene material is very inhomogeneous in its composition. We have to deal with the presence of varying amounts of decaying original organic and mineral matter, or the loss of both and the deposition of new minerals in an object. The biggest enemy for these fossils is a changing storage climate and desiccation. I have been working with this material for more than 25 years and would like to pass on my experiences. My presentation will give a brief overview of the destruction that can occur directly or over the years due to lack of, or even inappropriate, conservation. Understanding the condition of fossils is the key to choosing the right conservation method, even when restoring old collections. I will explain a conservation method using polyethylene glycol (PEG) and show how objects can be prepared in the field during excavation with a view to future conservation. Conservation with PEG has so far shown the best results with fresh finds. I will take a look at the destruction caused by other adhesives or solvents that I have come across during my restoration work and which are unfortunately still in use. Preserving these dry fossils from further damage and allowing them to be displayed is possible, but requires materials that are not reversible. Many old Pleistocene collections have been almost completely destroyed. This is why good conservation is so important for new finds.

From the seabed to museum display: on the palaeontological riches of the North Sea seabed between the British Isles and the Netherlands by Dick Mol

The woolly mammoth is the best-known symbol of the Ice Age, but northwestern Europe was also inhabited by woolly rhinoceroses, sabre-toothed cats and others during the Pleistocene. They inhabited the lowlands between the British Isles and the Netherlands and their remains are regularly found at the bottom of the North Sea where at the time the deltas of the Meuse, Rhine and Thames spread out over a large area - the so-called mammoth steppe. Although complete skeletons have never been found, hundreds of thousands of isolated bones and teeth of land mammals are known from this rich site, a site that is unparalleled. Many different animals and plants are known from the mammoth fauna that once inhabited these lowlands, thanks to intensive cooperation with the fisheries in the North Sea today. In addition to animal remains, there are also many indications that humans were part of this mammoth fauna, and survived for a long time until the North Sea reached its current level around 8,000 years ago.

| I will discuss the securing of Pleistocene skeletal remains found as by-catch when by fishing, and also those that were fished up at sea during targeted expeditions. I will explain how these finds are desalinated, catalogued, prepared and identified and ultimately how they can be used for scientific research such as carbon-14 dating, aDNA research, etc. Because of the enormous quantities discovered, these finds can also make attractive museum exhibitions that can demonstrate the biodiversity of the various extinct ecosystems of the Pleistocene. |  |

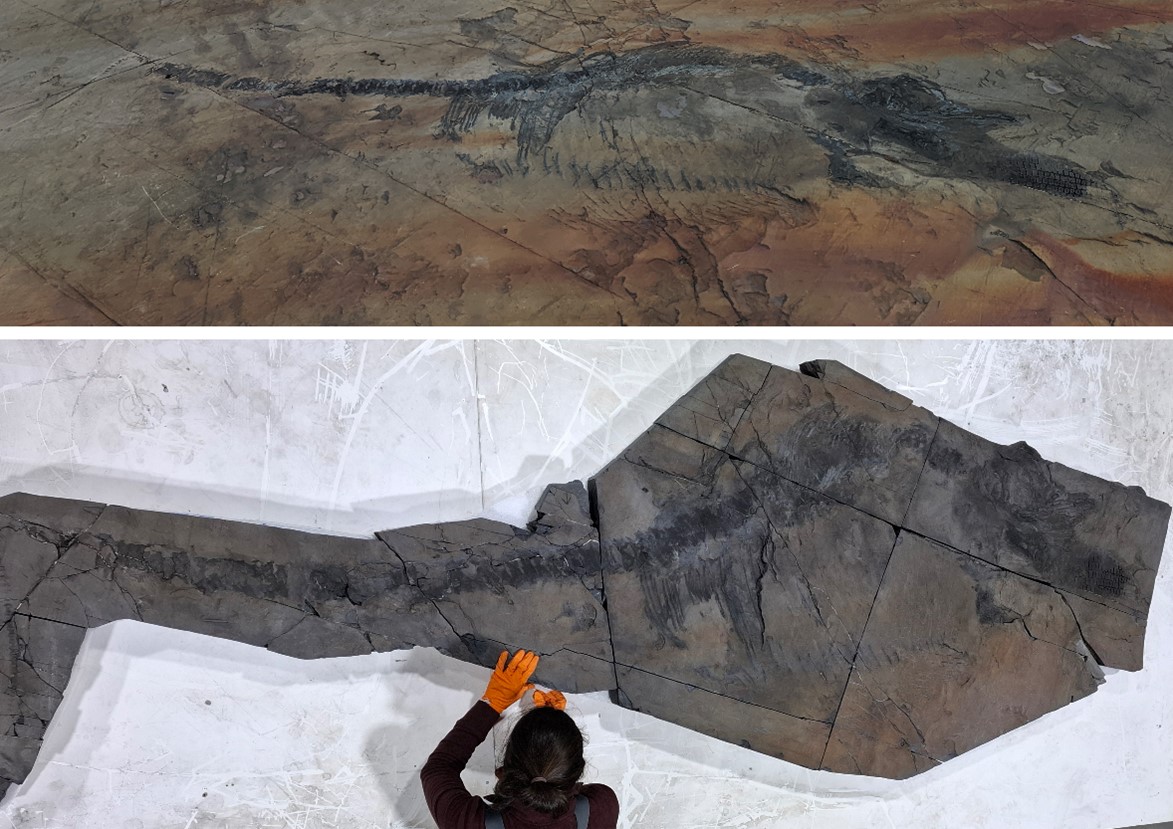

From field to lab: preparation of vertebrate fossils from a new Barremian Lagerstätte in South Lebanon by Nathan Vallée-Gillette, Dany Azar, Léa De Brito, Lionel Cavin, Pascal Godefroit, George Heneine, Sibelle Maksoud, Sébastien Olive, Kévin Rey and Ninon Robin

Lebanon is renowned for its rich Cenomanian fossil deposits, but recently its Lower Cretaceous deposits have also yielded significant fossils of plants, vertebrates and arthropods. In particular, the Barremian dysodiles (oil-shale mudstone) of Jdeidet Bkassine (Jezzine District, South Lebanon) are revealing vertebrate fossils of exceptional preservation. Until 2021, several surveys led to the discovery of ray-finned fishes, turtles and two complete mawsoniid coelacanths. In light of these promising finds, a two-week excavation was organised in 2023, supported by a National Geographic Society grant and involving an international team from Belgium, France, Lebanon, and Switzerland. The soft, easily delaminated shales allowed meticulous layer-by-layer investigation. A temporary preparation lab was set up on site to stabilise specimens, alongside identification and micro-sampling for geochemical analyses. This fieldwork unearthed an impressive array of vertebrates: coelacanths, an anuran, pleurodiran turtles, squamates, and 5–7 different groups of actinopterygians. The most promising specimens were CT-scanned at the RBINS, offering invaluable insights for preparation and taxonomy. The introduction of an air abrasive unit using sodium bicarbonate and iron powder revolutionised the preparation workflow - dramatically improving speed and precision while preserving fine anatomical details, reducing the need for invasive tools like needles or airscribes.

|

Many specimens remain to be prepared, some with exciting technical challenges. Yet the combination of exceptional preservation, with advanced 3D imaging, and refined preparation has improved our understanding of macrosemiid and mawsoniid anatomy. We hope these finds should soon enough be on display in Lebanon, to share this remarkable Lagerstätte with the public. |

Mounting meteorites: behind the scenes challenges for the NHM Space exhibition by Joeske Voets and Lu Allington-Jones

This presentation explores the challenges faced by the display and conservation teams when preparing specimens for the new exhibition “Space: Could Life Exist Beyond Earth?” at the Natural History Museum in London, UK. Most of these revolved around the need to prevent or minimise contamination, and measures were far more extreme than for other types of geological collections. Strategies included minimising contamination by making mounts around 3D prints and severely limiting the types of mount materials that can be used in contact with specimens. For the display cases there were strict limits on what materials, including other specimens, could be displayed together. For selected specimens, glass desiccators were used within display cases to maintain anoxic microenvironments. Some specimens were so tiny that a magnifying glass was included in the mount, whilst others were so heavy that it was necessary to check the floor-loading capacity. The exhibition even included a piece of driveway where one of the meteorites on display had landed. For most of the meteorites no remedial treatments were allowed due to the risk of contamination, but some were deemed to have already been compromised. For these, interventive conservation techniques were adapted from traditional commercial solutions for metal cleaning.

Poster Abstracts

A unique marine mammal locality: from discovery to exhibition by Klaas Post, Jordi Kempers, Remie Bakker, Hidde Bakker & Bram Langeveld

In 2014, a palaeontological survey of the Westerschelde estuary (SW Netherlands) by the Natural History Museum Rotterdam discovered a unique fossil site at a depth of 25 meters below the water table: an area of just a few hundred square metres in the middle of a shipping lane. Using a modified beam trawler, it was sampled over five years, yielding numerous large glauconitic sandstone concretions, weighing up to 500 kg. The concretions contained immaculately preserved skulls and post-crania of marine mammals. Many (partial) specimens were still in anatomical position or showed only limited post-mortem disturbance. Using diamond saws and pneumatic scribes, the fossils were prepared over the course of eight years. Each concretion took some 200-250 hours of careful work, as the fossil bones were weaker than the surrounding rock. After preparation, they were stabilized using Paraloid B72.

|

Analysis revealed skulls of four species new to science: pontoporiid Scaldiporia vandokkumi Post et al., 2017, cetotheriid Tranatocetus maregermanicum Marx et al., 2019, balaenopterid Nehalaennia devossi Bisconti et al., 2019 and several skulls of an as yet unnamed ziphiid. Dinocysts dated them to 8.7 to 7.5 Ma. This unique fauna inspired several palaeoartistic reconstructions of the individual whale species and the fauna as a whole, both in 2D and 3D. After careful consideration, the holotype skulls were put on permanent display in a new, dedicated exhibition at the Natural History Museum Rotterdam. Two of the specimens even made it onto postage stamps, issued officially by the Dutch postal service. |

Methodological proposal for the conservation of palaeontological ivory – an integrated case of collection care: from diagnostic assessment to preventive storage by Giselle Lorena Niño Silva

Fossil ivory presents complex conservation challenges due to its biological origin, diagenetic alterations, and environmental fragility. This poster presents a methodological proposal for the conservation and restoration of paleontological ivory. The method is structured in four stages: 1) taphonomic understanding, 2) material characterization, 3) diagnostic analysis, and 4) strategic planning of intervention. Each stage considers the scientific value, physical condition, and principles guiding conservation regarding stabilization, restoration, and display. Applied to a Pleistocene fossil ivory specimen from northeastern Mexico, the methodology demonstrated its relevance in guiding ethical and reversible treatments.

| Visual elements in the poster include the step-by-step workflow, alteration mapping, and examples of intervention strategies. The proposal aims to provide fossil preparators, conservators, and exhibition professionals with a systematic framework that respects both the scientific integrity and material stability of palaeontological specimens. This model was tested through the study and treatment planning of Pleistocene ivory from northeastern Mexico addressing complex material cases while fostering dialogue around best practices in the field. |  |

The Brymbo Fossil Forest: excavating, curating, conserving and interpreting a 300-million-year-old fossilised forest as a hybrid scientific endeavor and visitor attraction by Dr Tim Astrop

The Brymbo Fossil Forest is part of an exciting new heritage attraction (Stori Brymbo) in Wrexham, North Wales (UK). An in-situ Carboniferous forest consisting of lycopod tree-stumps with attached stigmarian root-systems, standing giant Equisetum thickets and abundant pteridosperm remains. The site is partially covered by a bespoke building that allows year-round excavation and study by a team of students and volunteers all while being publicly accessible as a unique natural history attraction. The Fossil Forest presents both amazing discoveries and novel challenges: how do you excavate, stabilise and present in-situ fossils in a way that both preserves scientific fidelity and effectively communicates the find to the public? How do you deal with trans-stratigraphical finds that obscure the discovery of other fossil material? And how do you record fossil finds in three dimensions for academic provenance? This poster presents some of the solutions we have found and best practices we have developed in the short time we have been operating, in the hopes of contributing to future endeavors in making palaeontology more accessible to a wider audience.

|

The Triceratops herd: from excavation to exhibition by The iconic dinosaur Triceratops, famous for its robust cranial parts, is usually found as a single, isolated specimen. Theories arose of the Triceratops being a solitary animal in contrast with other ceratopsids that do have remains of many individuals. In 2013, the Darnell Bonebed was discovered, which contained both cranial and postcranial elements of multiple Triceratops. This find is perfect for research on possible gregarious behaviour of Triceratops. The many (~1500) bones discovered raise challenges regarding preparation (bones in close proximity requiring heavy weighted plaster jackets) and correctly associating the right individual for every bone. After preparation, bones are analysed with a 3D-modeling program (Blender) for a correct size estimate and assigned to an individual. This decade-long project culminated in the first Triceratops herd on exhibition. |

|

Preparator-friendly field jacketing techniques by Tetsuya Sato

Field jacketing has been a fundamental practice in fossil excavation for over a century. Experienced field workers understand the importance of avoiding common mistakes—such as missing separators, poorly mixed plaster, or weak structures that can compromise a jacket’s effectiveness. However, even well-constructed jackets may present challenges for preparators in a lab. Since 2016, the American Museum of Natural History’s Morrison Formation excavation in Wyoming has yielded more than 150 small-to-medium-sized jackets, providing valuable insights into refining techniques. The focus is on creating preparator-friendly jackets that open easily without damaging fossils, provide adequate support during matrix removal, and feature clearly labeled critical information directly on the surface. To ensure fossils are safely accessed, incorporating a rim of plaster and separators on the opening side allows for a more controlled and damage-free opening. Reinforcing medium-sized jackets with wooden supports on the non- opening side increases stability without adding the excessive weight of plaster. Using two different separators for fossils and matrix creates a visual signal to indicate when preparators are approaching fossils. Clearly marking the orientation of exposed fossils, alongside key information such as field numbers, directly on the jacket helps prevent unintended damage, supported by photos taken in the field.

The chemical treatment of pyrite oxidation: a comparison of methodologies by Océane Lapauze, Kieran Miles and Martin Krogmann

The chemical treatment of geological specimens affected by pyrite oxidation typically involves the use of either ammonia or ethanolamine thioglycolate, but the methods by which they are used vary from institution to institution.

|

Several methodologies are presented here for comparison, methods currently in use at the Natural History Museum (London), the Natural History Museum of Basel and the University of Bremen.These include the use of dry ammonia gas in a vacuum followed by coating with paraffin, exposure to vapour of ammonium hydroxide mixed with PEG 400, and the use of ethanolamine thioglycolate by the application of gel, paste or full immersion in solution. These examples will hopefully be of use to anyone struggling with the care of at-risk collections, who may decide to implement one or more of these depending on the space, budget and layout available to the individual or institution. |

Preparing large ammonites for garden display by Kieran Miles

The Urban Nature Project, a complete redevelopment of the gardens of the Natural History Museum in London, was completed in the summer of 2024. Several large ammonites from the Late Jurassic Portland Stone Formation (Tithonian, approx. 150 – 145 Ma) were sourced from Chicksgrove quarry, Wiltshire, the largest of which was almost 0.8 metres across and weighed 150kg before preparation.

| These specimens were prepared for display in the gardens, with the objective that the final result would be both aesthetically pleasing and as naturalistic as possible. Bulk matrix was removed by hammer and chisel, and the inner whorls were prepared by an air scribe (HW 70) fitted with a chisel stylus. Several methods were tried to obscure tool marks, including the use of very dilute acetic acid. Finally, the fossils were sprayed with nanolime to help withstand the effects of weathering. The specimens will be regularly monitored to assess the effectiveness of this treatment. |  |

From excavation to exhibition within 10 years (hopefully!): the ‘Rutland Ichthyosaur’ from Rutland, UK by Nigel Larkin

An almost complete 10m-long Temnodontosaurus ichthyosaur skeleton was discovered in January 2021 in shallow water at Rutland Water Nature Reserve in the UK. This was excavated by a small team of palaeontologists just 7 months later, when water levels were low enough. Nicknamed ‘The Rutland Sea Dragon’, the specimen was analysed in situ, recorded, and excavated in a series of large plaster field jackets to preserve taphonomic information etc. Significantly, the specimen is the largest ichthyosaur skeleton to have been found in the UK, is almost complete and is the first Temnodontosaurus trigonodon to be found in the country, extending the known geographic range of the species significantly.

For almost four years the specimen has remained in storage, preserved and protected in its field jackets, whilst funding issues are resolved so that the next phase of work can commence: the 2.5 year project to de-jacket, prepare, conserve, record and mount the specimen for display. Extensive research will be undertaken during this phase and the specimen will be 3D scanned in detail. This work should be completed by autumn 2027.

The specimen will go on display in Rutland County Museum, which is conveniently located only one mile from the site where the skeleton had lain for 182 million years! However, the specimen is so large that there will have to be a significant project to redevelop the museum building to accommodate it, requiring fundraising and significant building works. The specimen will be ready for display before the building work is completed.

From excavation to exhibition within six months: the ‘Mammoth Graveyard’ at Cerney Wick in Gloucestershire, UK. Powered by volunteers! by Nigel Larkin, Sally Hollingworth and Neville Hollingworth

Cerney Wick in Gloucestershire, UK, is a nationally significant palaeontological site that has produced a rich vertebrate assemblage (including mammoth, rhino and bovid bones as well as flint handaxes) from a buried river channel that is over 200,000 years old. In addition, the underlying Jurassic Kellaways Sand Formation has yielded exceptionally well-preserved fossils (about 165 million years old) that provide new information on the stratigraphy of the area. The site offered an unrivalled opportunity for the palaeontological and archaeological communities to work together to understand the context and significance of this site and the evolution of the Upper Thames Valley during the Pleistocene and recover unique fossils and stone tools from an area that had not been comprehensively investigated. The aim of the 2024 excavation was to build on previous work in the area, and specifically to provide training for students in fieldwork and onsite conservation techniques. The recovered material will be donated to appropriate local museums for research and display as an important part of our nation’s geological and archaeological heritage. This will raise awareness of the significance of this site and highlight the vital role of sand and gravel quarrying in the Cotswold Lakes area - without which such sites would not be discovered. Within six months of the 2024 excavation (which involved 180 volunteers over three weeks), the finds were conserved, prepared and put on temporary display in the nearby Corinium Museum in Cirencester. This work was undertaken by the team of volunteers and the exhibition was a resounding success.

From excavation to exhibition within 50 years: the ‘Maidenhall Mammoth’ from Ipswich, Suffolk, UK by Nigel Larkin and Simon Jackson

In 1975, whilst digging trenches for sewage pipes at Stoke High School at Maidenhall in Ipswich, UK, the partial skeleton of a Steppe Mammoth (Mammuthus trogontherii) was discovered along with the disarticulated remains of other ice age animals. An excavation the following year recovered even more material. Known as the ‘Maidenhall Mammoth’, the skeleton comes from an interglacial period (Marine Isotope Stage 7) about 200,000 years ago. It is one of the most complete examples of its species from this period, but with a shoulder height of only 2 m it is the smallest example of its kind known from Britain. Along with evidence from elsewhere in Britain, it indicates that the species shrunk significantly from a much larger 4 m shoulder height 500,000 years before.

A small selection of bones from the skeleton were on display at the local Ipswich Museum for almost 30 years as well as at the school in Maidenhall for 6 years. As part of the complete redevelopment of Ipswich Museum currently taking place, with an opening date in 2026, the whole skeleton will finally go on permanent display, along with other associated remains. This will require many months’ work to clean, consolidate and repair many dozens of bones that are quite fragile and then mount them. The skeleton will be presented on a tilted plinth, lying on its side as if still being excavated. This will be the first time that all the bones of the skeleton have been reunited in 50 years.

|

The geological preparation apprenticeship program at the University of Münster by Davina Mathijssen A unique, three-year training opportunity, accepting one student per year. It is one of only three such programs in Germany, making it particularly exclusive. The program provides comprehensive training in geological sample preparation, including macro- and microfossil preparation and the production of thin sections. Apprentices learn both traditional and modern techniques under the guidance of experienced professionals and work at the interface of university and museum. Combining practical skills with geological knowledge, the program prepares graduates for careers in research institutions, museums, or geoscience labs. The University of Münster offers an excellent foundation for a specialized career in geological preparation. Davina Mathijssen |

|

What is SPPC?

The SPPC is intended as a forum in which professionals, amateurs and researchers alike, interested in all aspects of preparation, conservation, model-making and related subjects, can participate. The SPPC offers a unique opportunity to meet friends and colleagues and to discuss recent developments, ongoing research, and other, often museum related, projects. Although the SPPC generally precedes the the SVPCA conference, contributions are not limited to the field of vertebrate palaeontology.

SPPC Conferences have been run since 1992, either before or after the SVPCA, and many participants attend both conferences. Over recent years the number of talks on offer has been in decline, and there is a need for discussion on the nature and identity of this event. Conferences are held in a variety of venues, and offer a great opportunity both to share experience and to have the chance to look over the facilities other organisations and how they are used.

SPPC abstract archive

This section contains a listing of talks and posters delivered at SPPC in previous years. If you are wondering what SPPC is all about, or if it is for you, then this is a good place to start. The abstracts are organised by year - if you are looking for a specific abstract, then please try using the search function in the right hand menu of the website.

We particularly encourage you to check out the following links:

- A full listing of abstracts previously presented, from 1992 to the present

- Posters and video from our 2020 virtual event

- Posters from our virtual event held in 2021

- Posters and talk abstracts from 2022

- Posters and talk abstracts from 2023

- Posters and talk abstracts from 2024